What I'm reading on governance & conflict - #23

Grievance states, the unintended consequences of anti-corruption & security interventions, gender & power, the Godfather & foreign policy, the joy of an Irish accent and much more...

I’d say this is a back to normal ‘what I’m reading…’, but not much feels very normal right now. For every green shoot of hope - the US election result, the possibility of a Covid vaccine, tons of great investigative journalism being recognised in the shortlisting for the British Journalism Awards - there are some awful things happening too: the beheading of as many as 50 people, including children, in Mozambique by militants; Ethiopia looking to be on the brink of civil war, only one year after Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed won the Nobel Peace prize (the Nobel committee are starting to have form on this…); and political/corruption/organised crime-related attacks on journalists in Mexico, the Philippines, Zimbabwe and many other places. Nothing is ‘normal’.

I’m going to start with some tv in here rather than in the ‘Just for Fun’ section. I included the French spy series ‘The Bureau’ in a previous edition, and season 4 finds Malotrou, the main character, hiding out in Moscow, with a whole plot around AI and offensive cyber capability, but there’s a different story line that I can’t shake today. It finds Jonas, a normally desk-bound analyst from the Syria desk, in the field trying to locate Jihadists to gather intelligence. In episode 6, he is with a group of Yazidi women fighters who help him find a target. One woman in the group never speaks, and he’s told that sometimes the trauma that women suffered under Daesh is so awful they can’t find any words for it. I won’t say more about the storyline, but it is one of the most devastating expressions of the trauma of conflict I’ve ever seen in a fictional setting. This recent article on one woman’s experiences gives a glimpse of this pain, as does this research on how Yazidi women are ‘liberated, not free’, with the community as well as individuals continuing to try to deal with ongoing trauma and displacement.

An interesting take on geopolitics that I’d missed is the creation of so-called ‘grievance states’ by the US State Department in late 2019, which are said to share ‘four basic characteristics: (1) a sense of self-identity powerfully rooted in affronted grandeur; (2) oppositional postures to what is said to be malevolent foreign influences; (3) a need for foreign enemies to justify domestic authoritarianism; and (4) a revisionist sense of geopolitical mission in the world.’ Recent analysis by Ayjaz Wani looks at how a Biden administration might engage with Central Asia, moving beyond the current administration’s strategy for the region that’s heavily grounded in ‘grievance states’ geostrategy, as well as the role that India could play in this.

Some interesting analysis from Benjamin Fogel on corruption in South Africa and ‘A cycle of diminishing expectations’. He looks at how the government is cracking down on corrupt politicians as the Zondo Commission ‘state capture’ during former President Jacob Zuma’s tenure provides regular revelations about the capture of the state by private interests. With COVID-19 causing economic, social and political challenges, it may be that the South African public has had enough, but Fogel makes a compelling case for how this needs genuine attention to be paid to state capacity and to what Caryn Peiffer and I call ‘corruption functionality’, or ‘the ways in which corruption provides solutions to the everyday problems people face, particularly in resource-scarce environments, problems that often have deep social, structural, economic and political roots’ (coming soon to Global Integrity ACE). As Fogel writes: ‘[R]educing the question of anticorruption merely to prosecuting the corrupt, as cathartic as it is, can have unintended consequences and in some cases make things worse. Corruption cannot simply be solved through technical fixes and increasing “accountability” by locking up the villains’. The state actually needs to be able to provide what people need, and the public need to trust that this is the case.

Speaking of corruption functionality and unintended consequences, I have a new article out 🎉 with Caryn Peiffer, Rosita Armytage & Pius Gumisiriza on ‘Lessons from reducing bribery in Uganda’s health services’. Our research showed that almost half of all people who made contact with the health sector in Uganda in 2010 paid a bribe, but by 2015 this rate was just 25% - an almost unprecedented reduction, especially in such a short time frame. Much of the credit for this decrease goes to the Health Monitoring Unit (HMU), launched in 2009. Among other things, the HMU carried out unannounced investigations in health facilities, often to investigate bribery complaints, including public ‘naming and shaming’ of frontline health workers for engaging in corruption. While the approach clearly worked in terms of reducing bribery, there are serious questions about sustainability and unintended consequences, both linked to corruption functionality. The aggressive nature of the intervention also led to a huge nation-wide strike and loss of staff morale and public trust. Their approach also didn’t take into account the everyday reality that bribery supplements very low wages in the public health sector. Despite humiliation and fear, health workers simply couldn’t survive on their wages alone, with bribery patterns re-emerged with different patterns, a trend also observed by Claudia Baez Camargo & Lucy Koechlin in their FCDO-funded research on Uganda, Rwanda and Tanzania. This raises questions about what the HMU’s actual goal was: Was it reducing bribery, or was it improving service delivery and health outcomes? In other words, should we be thinking about anti-corruption interventions as ends in themselves, or as means to other important ends?

Writing for the US Institute of Peace, Emily Cole and Allison Grossman write about how the US, France and the EU have invested a lot in the Sahel in terms of tackling perceived transnational threats such as violent extremism and migration, but this has come at the cost of undermining countries’ own interests and long-term stability. By skewing investment so much towards foreign security interests, they argue how ‘these investments undermine democratic accountability, distort policy priorities, and encourage corruption among political elites’. They provide a number of urgent recommendations, including how donors need to prioritise the concerns of people living in the region, particularly around provision of basic services, as well as ensuring that security assistance is transparent, that all security actors are accountable for their actions and that political leaders aren’t pressurised into putting more money into security rather than the service delivery the public so desperately needs.

A recent paper looks at ‘measuring diplomatic capacity as a source of national power’ to help ‘illuminate the scope of countries’ diplomatic activities and resources, the reasons some countries place priorities on certain resources over others, which countries have outsized diplomatic influence beyond those predicted by their measured capacity, and the significance of other characteristics that indirectly impact diplomatic importance’. In other words, diplomatic capacity can be measured, unlike power or leverage, but it isn’t something countries have; it is instead the direct result of political priorities set and choices made. Diplomatic capacity can be decreased as well as increased as a result of these choices, as well as through unintended consequences. The authors are in the process of producing a new index that quantifies the resources and tools that countries dedicate to diplomatic activities, and propose four main subcategories: political, economic, security and public diplomacy. They also include a number of important caveats to consider that align well with what we already know from existing evidence on governance and conflict indicators.

Priya Chattier and Leisa Gibson fly the flag for getting gender back into the political economy analysis discourse. I’m going to have a ranting moment here…HOW MANY TIMES DO PEOPLE HAVE TO SAY THAT POLITICS AND POWER ARE ALWAYS GENDERED?! As Priya and Leisa say, we need to be unapologetic about this, ‘Because there is still a degree of “please”, “sorry but I have to say this” and “forgive me” surrounding raising of gender issues in some government and governance circles (although thankfully fewer and fewer over time)’. So no apologies for my uncharacteristic all-caps moment, and seriously - it’s been 6 years since Evie Browne’s brilliant blog for DLP on ‘Gender: the power relationship that political economy analysis forgot’ where Evie herself stood on the shoulders of so many giants who have been saying this for decades. Deep breath. I look forward to their forthcoming paper on ‘Gender responsive PEA’.

Like probably most people who study corruption and organised crime, I’ve long been a big fan of ‘The Godfather’ (book and films), and I enjoyed this piece from Jonathan Freedland on ‘how the Mafia blockbuster because a political handbook’. He writes about how it is a literal handbook for at least one MP, but others clearly use it as well. He also looks at The Godfather Doctrine, a book on foreign policy drawing parallels with the story. As Freedland describes,

One camp, the authors explain, are liberal institutionalists, who follow the lead of adoptive brother Tom Hagen: they believe the old order still holds and that negotiation is the answer. Opposite them stand the hawks of neoconservatism who, like the eldest son, Sonny Corleone, believe that a massive show of force is the only way to retain top spot in the new landscape. Finally, there are the realists who, just like Michael, understand that it is only the combination of strength, judiciously deployed, and patient diplomacy that will bring lasting security. You don’t have to buy the analogy to agree that it’s a rare kind of bestseller that can spawn a foreign policy monograph some four decades after publication.

The fab team from the FCDO-funded research project on procurement ‘red flags’ & corruption have a new article out on ‘Controlling corruption in development aid: new evidence from contract-level data’. Drawing on data on donor-funded procurement contracts in 100+ countries in 1998–2008, they find that ‘an intervention which increases donor oversight and widens access to tenders is effective in reducing corruption risks: lowering single bidding on competitive markets by 3.6–4.3 percentage points’. They also find that this effect is greater in countries with low-state capacity, which is promising.

Thomas Bollyky, Sawyer Crosby & Samantha Kiernon have a short piece on how ‘Fighting a pandemic requires trust’, with this great, if depressing quote:

Some national leaders have failed to appreciate the importance of having a government that citizens trust and listen to. That failure has contributed to vast differences in countries’ performances in this pandemic and threatens to make everyone less safe when the next pandemic threat emerges, as it inevitably will.

This aligns well with what Sian Herbert and I have found in the wider evidence on COVID-19 and isn’t dependent on one type of political regime or another (paper out soon…I promise!). As Francis Fukuyama argued early on in the crisis, it will ultimately be ‘the state’s capacity and, above all, trust in government’ that will determine how effective COVID-19 responses are, especially ‘whether citizens trust their leaders, and whether those leaders preside over a competent and effective state’, a conclusion borne out by the wider evidence.

Finally, I’ve been asked recently to talk at a number of different events about political will and organised crime/corruption, and I find this short video based our synthesis of 10 years of DLP research really useful at helping get across how coalitions can help with getting traction and, then, political will for difficult reforms. (More political will reading to come, I’m sure…)

Shorts…

A new ‘PEA update’ on ‘Putting TWP, PDIA, DDD and AM into Practice (or, more colloquially, what these tongue twister terms mean and why they matter)’

Oliver Bullough’s weekly kleptocracy round up on ‘Citizens on the cheap and London real estate for a pretty penny’ (someday, hopefully in the not too distant future, we’ll look back at these practices and think about just how crazy they were…)

Sam Hickey & Tim Kelsall from the FCDO-funded Effective States & Inclusive Development programme on ‘The Three Cs of inclusive development: context, capacity and coalitions’

Tom Carothers with a US ‘Postelection forecast: more polarization ahead’, which is good to read alongside Peter Geoghegan’s ‘How Trump was able to attack democracy - and pick up 70m votes’, Fintan O’Toole’s ‘Democracy’s afterlife’ and what he calls ‘zombie politics’ and an oldie but goodie from John Harris on ‘The lesson of Trump and Brexit: a society too complex for its people risks everything’

Another oldie but goodie that’s always worth rereading from time to time because it remains perennially useful, no less so than now with COVID-19 - Kent Weaver’s classic 1986 paper on ‘The politics of blame avoidance’

Emily Kallaur & Stephen Davenport writing for the World Bank on ‘Fighting corruption through Open Government Initiatives’

Tax Justice Network on how the ‘OECD’s “tax haven lite” blueprint fails pandemic-gripped world’

Amy Zegart on how ‘Intelligence isn’t just for governments anymore’ and how spy agencies need to get better at connecting with the public, especially as technology increasingly impacts the security of public life

Grant Walton’s thoughtful article on ‘Establishing and maintaining the technical anti-corruption assemblage: the Solomon Islands experience’ and how transnational coalitions of donors and various international and national actors help to ‘maintain the technical and apolitical nature of anti-corruption reform’

Claudia Gastrow on ‘Laundering Isabel dos Santos’ and the global enablers of kleptocracy

Noah Smith on how ‘China has a few things to teach the US economy’

Julia Stanyard on ‘Gangs in lockdown: Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on gangs in east and southern Africa’, which is good to read with Insight Crime’s ‘COVID-19: Gangs, statemaking, threats and opportunities’

Alexandra Reid, Rob Parry-Jones & Tom Keatinge on ‘Targeting corruption and its proceeds: Why we should mainstream an anti-corruption perspective into “follow the money” approaches to natural resource crime’

An important ‘long read’ from Martin Chulov on ‘How Syria’s disinformation wars destroyed the co-founder of the White Helmets’

Amartya Sen on ‘As India drifts in autocracy, Gandhi is inspiring students’ nonviolent resistance’

Ashish Kothari with a ‘COVID-19 Pandemic: Worlds Stories from the Margins’ on ‘What does self-reliance really mean? Amazing stories from India’s margins’

This piece from Caroline Cassidy on how ‘Change is all about the narrative’ is a great short read on the use of framing, emotion and all sorts of other things in developing effective change narratives

I miss sitting with co-authors and writing (looking at you, Dr Peiffer, in particular), so this article on virtual writing retreats and how they make you happier and more productive is well-timed.

Just for fun…

We watched a BBC series on ‘The Secret History of Writing’ that was fascinating 🤓. Episode 1 is sadly no longer available on iPlayer, but they showed how the Latin alphabet (used in English, for example) is a direct descendent of Egyptian hieroglyphs, as are many others. This animated version tells the same story, with part 1 getting you as far as ancient Greece and then further videos taking it from there to Rome and then beyond. The cartoons don’t have quite the same ‘wow’ factor as seeing the letters drawn by talented calligraphers showing the whole process, but it’s still pretty amazing.

Someone shared this trailer on Twitter saying that it’s the best Saturday Night Live skit ever, and I watched it waiting for the punchline that never came. The reaction to some of the less than convincing Irish accents (let alone…well, everything else) has produced some real gems, including the Leprechaun Museum tweeting: ‘Even we think this is a bit much #WildMountainThyme’.

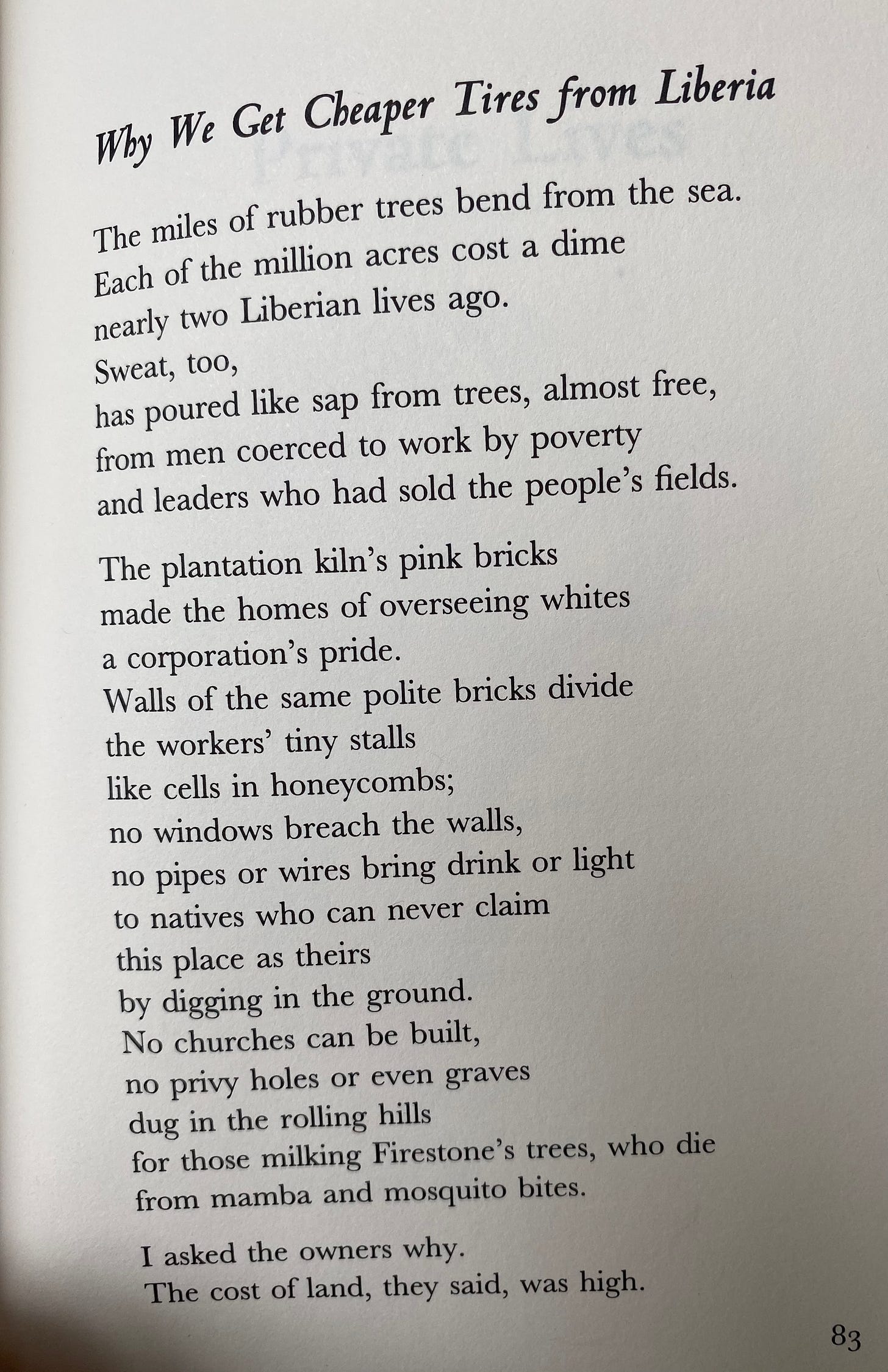

It was Jimmy Carter’s 94th birthday recently. He’s the first US president I remember and is still an inspiration. My former boss bought me a book of his poetry (Always a Reckoning) when I graduated from my undergraduate degree, and this simple poem is on the list of things that inspired me to do what I do…

Finally, my almost 13-year old is currently watching ‘How to Train a Dragon’ and laughing as I write this, but I can’t help but think how hard it has been for parents in 2020 trying to keep our kids going emotionally this year. I’m more conscious about not talking about all the bad stuff I read and think about when it’s out of school hours, and this means my time on whatsapp has definitely increased as I connect with friends and colleagues. There’s nothing like sharing worries, debating big issues and enjoying some high quality gifs to keep you going through the darkening months. 🙏